When surgery fails

The analysis of what has gone wrong when carpal tunnel surgery has not worked is often challenging, especially so if you did not meet the patient before surgery. My usual strategy is as follows.

Was it CTS to begin with? Try to obtain a retrospective history of what the symptoms used to be like before surgical interference. Were any confirmatory tests carried out and what were their results, especially NCS and imaging studies. If the history suggests another diagnosis can that be confirmed with investigations now?

Has the character of the symptoms changed after surgery or is it still a case of more or less of the same thing the patient had before operation? A marked change in the type of symptom present can be a clue either to development of an operative complication or of new pathology entirely. There is however a caveat to this - a marked deterioration in median nerve function can result in a change in the character of the symptoms from ‘positive’ symptoms of tingling and pain to ‘negative’ symptoms of numbness and weakness and occasionally the converse is true with the symptoms actually becoming more troublesome because median nerve function has improved.

Has the distribution of the symptoms changed? Again a change in the pattern of fingers involved can be a clue to nerve injury during surgery or the presence of an entirely different nerve problem.

Is the problem now CTS? Remember that patients who get CTS are also predisposed to trigger finger and Dupuytrens contracture and that Raynaud’s phenomenon, arthritis of the metacarpophalangeal joint of the thumb and cervical radiculopathy are also very common conditions and sometimes coexist with CTS.

If it appears that the pre-operative diagnosis was correct and that the current symptoms and signs still suggest median nerve dysfunction then the main question to be asked is ‘Was the transverse carpal ligament fully sectioned?’ It is important to establish this because the main decision to be made is whether to make a second attempt at surgery. Partial division of the transverse carpal ligament is a relatively common surgical mistake (108 out of 200 failed operations in one series - Stutz 2006) and is correctable at a second operation.... but one does not want to operate a second time if there is nothing more to be achieved other than giving the patient more of a scar. Two investigations can help here:-

a) If the nerve conduction studies show deterioration compared with pre-operative studies then incomplete division is quite likely. If they show improvement, any improvement, then the ligament has almost always been divided adequately. If they are unchanged then again, incomplete division is likely, except in the case of a nerve which was Canterbury grade 6 before surgery and is still grade 6 after. These patients are unlikely to benefit from further surgery whether the ligament has been divided or not but we have seen one exception to this. Of course to be able to make these comparisons you do need up-to-date pre-operative nerve conduction results, preferably recorded during the three months prior to surgery. The presence of a nerve conduction abnormality after surgery does not, of itself, indicate persistent nerve entrapment because many patients with entirely successful surgery show considerable residual impairment of median nerve conduction when they are tested afterwards, even though they have no symptoms.

b) ultrasound imaging - this can show pictures which are very suggestive of a remaining band of undivided transverse carpal ligament but I am still in the process of evaluating this technique at present.

If we are satisfied that there is not an undivided section of transverse carpal ligament then is there another indication for re-operation? It has been suggested that microsurgical dissection of fibrous tissue from the nerve (external and internal neurolysis) can benefit some patients and that various procedures designed to provide extra protection for the median nerve by interposing other tissues between the nerve and the skin may be helpful for post-operative pain. There is little hard evidence to support such interventions and an expert hand surgeon should be consulted if the pattern of post-operative symptoms suggests that they may achieve something.

Injection after surgery?

There is now a paper which gives us a little information about whether it is worth trying local injection after surgery (Beck 2012). These authors were interested in whether the response to an injection might help to predict the outcome of revision surgery and they tried an injection of 3.3 mg lignocaine, 6.6 mg methyprednisolone and 1.3 mg dexamethasone in 28 hands with persistent or recurrent symptoms after carpal tunnel decompression before going on to re-operate on them. 23 of the 28 hands improved with injection and 20 of these improved with the second operation whereas of the 5 who did not respond to injection 3 did respond to surgery. Although this is a difference of 87% success vs 60% success, with these small numbers this is not statistically significant. 13 were found to have evidence of incomplete division of the flexor retinaculum at re-operation, similar to the study of Stutz et al, and 12 of these benefitted from the second operation. However 12 of the other 15 patients without obvious evidence of an undivided ligament also improved after re-operation and again this difference in outcome is not statistically significant.. There was also a poster at a recent AANEM meeting (2011) describing a patient who experienced benefit from injection after failed surgery.

Categorising patients with failed surgery

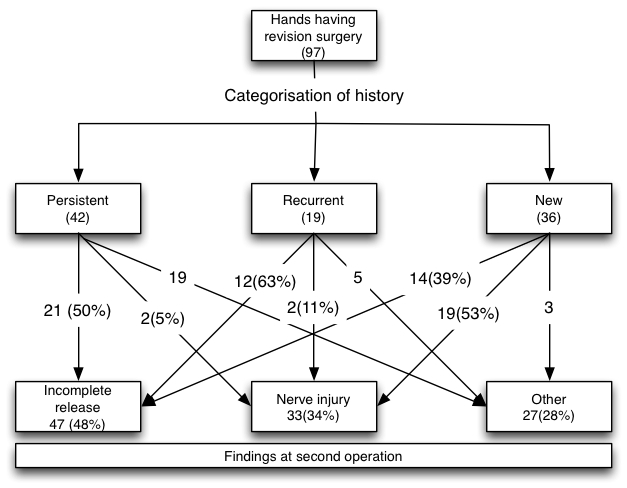

A new, large, retrospective study from St Louis (Zieske 2013) has looked at 97 revision carpal tunnel decompression operations in 87 patients. These authors have begun to tackle the problem of all patients having bad results being referred to as 'recurrent CTS'. They divided their problem hands into 'Persistent' - meaning the same problems continued as before surgery, 'Recurrent' - those who got better after the original operation and then developed symptoms again after an interval, and 'New' - those patient who had different symptoms immediately after surgery. This is a considerable advance on lumping all of these different types of story together but still fails to fully address the nuances of exactly how symptoms have changed after surgery in the 'Persistent' and 'New' groups. All of the patients in this study had had their first surgery at other institutions and relatively little is said in the paper about the use of either NCS or imaging to help analyse the problems - I suspect because they may not have had full records from the first operations. Nevertheless there is a good deal of useful information here. The most interesting finding is the way in which the three different types of clinical story relate to the observations during the revision operation:

Of the patients with immediate problems after surgery, the persistent group were more likely to have incomplete division of the transverse carpal ligament while the new group were more likely to have a nerve injury of some kind but neither of these observations were absolute rules - 2 patients with persistent symptoms were found to have nerve injuries and 14 with new symptoms had incomplete release. One can guess the explanations for these - a nerve injury can produce the same loss of function in a nerve as a severe compression and the symptoms of the two things may therefore be indistinguishable, and partial decompression of a nerve can influence function either for better or worse and thus change the type of symptoms being experienced.

The 'recurrent' group also had a high incidence of apparently intact transverse carpal ligament to be divided but it is not clear whether this is because the ligament was not divided to begin with or because it had re-formed.

Most patients in all three groups, 88% overall, showed evidence of scarring around the nerve and adhesions to surrounding structures and as this finding was more or less universal it was not a lot of help in either categorising the patients or predicting outcome.

For the results of the second operations the paper is less useful. The surgical outcomes are presented as the average improvements in visual analogue pain scores and grip strength measurements for each group of patients. For a patient considering having revision surgery this is less helpful in decision making than a success rate - what one really wishes to know is 'How many of these patients thought that the second operation was worth having and would do it again?'

18 of these hands had had two or more previous attempts at surgery and this proved to be a poor prognostic factor for a further attempt at revision. Curiously the 'persistent' group also seemed to have a greater risk and the group with nerve injuries a lesser risk, of complaining of worse pain after the revision procedure. A wide range of other factors were of no help in predicting the outcome of re-operating.

It is also interesting that the senior author of this paper has abandoned the use of interposed fat pads around the median nerve as an approach to trying to relieve pain after carpal tunnel decompression

---------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

If we are not dealing with persistent or recurrent CTS symptoms then the next thing to consider is whether the symptoms are recognisable as one of the known complications of carpal tunnel surgery? ‘Pillar pain’ is a deep seated discomfort in the wrist which can be aggravated by leaning heavily on the heel of the hand and which may be related to loss of the ability of the transverse carpal ligament to hold the bones of the carpus in an arch shape. Those who are interested in the biomechanical effects of surgical section of the transverse carpal ligament will find a very good review of the topic in Brooks 2003. This will often resolve in time and there is little evidence to suggest that reconstructing the transverse carpal ligament helps. Excessive tenderness and hypertrophy of the scar may respond to physical therapies and occasionally may require surgical revision of the scar. Injury to the palmar cutaneous branch of the median nerve leaving a painful neuroma may require surgical excision, and injury to the median nerve itself or the recurrent motor branch to the thenar eminence (rather more common and recognisable because the sensory symptoms have improved as expected but there is marked new weakness of the thumb) may require microsurgical repair, nerve grafting, or a ‘rescue’ procedure by means of a tendon transfer to restore thumb movement. Some patients develop thickening and deep tenderness either side of the scar at the heel of the hand, approximately in the region where one expects the cut ends of the transverse carpal ligament to lie, especially on the thumb side - the nature of this is uncertain but again most cases seem to settle slowly over time.

If surgical re-exploration of the wrist is indicated there is no agreed best time for this. I would tentatively suggest that the outcome of carpal tunnel release should be checked at two points. When the stitches are removed, usually at two weeks, if there has not been a marked improvement in sensory symptoms or there is new weakness of the thumb and the original CTS was Canterbury grade 4 or less then immediate NCS should be arranged (which will itself take 2-4 weeks in our department). Otherwise the patient should be reviewed at about 3 months and NCS performed if there has not been at least some improvement.

Revision date - 13th September 2013